An Eco-Student’s Guide to Healthy Schools

As we enter our fifth year of programming at Healthy Schools PA, we are BEYOND excited to introduce our “Eco-Student’s Guide to Healthy Schools” workbook. The workbook, designed to be a student companion to our Healthy Schools Recognition Program, is an interactive guided inquiry into the systems that keep our school buildings running.

Using an investigative journalism lens, and with the goal of promoting science communication skills and environmental health literacy, the workbook was designed to be used with upper elementary and middle school students.

The workbook is a tool to help students investigate and learn about the different ways our school interacts with the environment. Our school buildings and the ways we use it can impact both our planet and our health in different ways.

In other words: when we protect our environment, we are also protecting our health.

Across the country, schools are working towards a sustainable future. Sustainability in schools means using practices that meet our current needs without making it more difficult for people in the future to meet their own needs. Schools can make huge impacts on our environment due to their size, because it takes a lot of resources to keep our school buildings running, such as energy that comes from renewable and non-renewable sources, water that comes from our local rivers, and food to feed every student.

This workbook will not only help you determine the ways your school is impacting the environment, but also spark your own ideas for eco-friendly changes you can make in your home, classroom, school, and community. Even small actions, such as switching out light bulbs for more efficient ones, can make a HUGE difference! Every sustainable act is a step in the right direction for a sustainable future.

We hope you take a chance to explore our workbook and have an opportunity to use it in your own classroom!

Whole School, Whole Child, Whole Community & Other Theories that Inform Our Healthy Schools Work!

This month, we would like to take a deep dive into the theories that inform our public health practice. Theories help inform our work, guide our decision-making, and hold us accountable to a process that is equitable, inclusive, and responsible. When we’re thinking about improving the health, safety, and quality of the learning environments in our Pennsylvania schools, we want to be intentional in creating sustainable impacts and changing school cultures.

What does it mean when you say Healthy Schools is a public health program?

Public health is a discipline focused on preventing disease and promoting health for different populations of people. Instead of delivering care in a clinical setting, public health practitioners deliver care in a community setting. Instead of focusing on curing disease, public health practitioners spend most of their energy preventing disease through data collection, education, programming, and connecting families to resources. So when we say that Healthy Schools is a public health program, it means that we create programming that is based on the best available scientific evidence, that serves the entire school community, and that is focused on preventing environmental health hazards in the spaces where we grow, learn, play, and work.

Why do theories matter in public health programming?

Social and behavioral theories provide a framework for understanding why health disparities exist among different members in our communities. As an organization focused on protecting children’s health, we know that children are uniquely vulnerable to environmental hazards because of their developing bodies and behaviors. We want to reduce and eliminate the health risks so that children can have the best opportunity to thrive and grow.

For each theory below, we will break down its main components and discuss how we’re using theory to guide our principles in setting priorities and involving community members for Healthy Schools programming.

Whole School, Whole Child, Whole Community

According to the Centers for Disease Control, “The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child, or WSCC model, is CDC’s framework for addressing health in schools. The WSCC model is student-centered and emphasizes the role of the community in supporting the school, the connections between health and academic achievement and the importance of evidence-based school policies and practices. The WSCC model has 10 components:

- Physical education and physical activity.

- Nutrition environment and services.

- Health education.

- Social and emotional school climate.

- Physical environment.

- Health services.

- Counseling, psychological and social services.

- Employee wellness.

- Community involvement.

- Family engagement.

The Whole School, Whole Child, and Whole Community theory puts children’s health at the center. It focuses not only on what’s available to children – physical activity and health services, for example – but also what social supports are necessary for raising healthy children. Having other stakeholders involved, such as staff, teachers, parents, administrators, and community members really speaks to the proverb that ‘it takes a village to raise a child’. At Healthy Schools PA, we use this framework to map what assets and strengths are available to a specific school community, and which areas we need to invest and improve upon to support the health of the whole child, the whole school, and ultimately, the whole community!

Whole School Sustainability Framework

The Center for Green Schools, with other collaborative partners, first put forth the Whole School Sustainability Framework in 2016. According to the report, “The framework is founded on the imperative that in order to be successful, sustainability requires a whole-system approach.

A Whole-School Sustainability approach requires individuals from across an organization to work together—it cannot be accomplished in a silo. This system framework is organized into the three components of schools: organizational culture, physical place, and educational program. Within these three components, we have identified a total of nine principles. ”

At Healthy Schools PA, we know that in order to promote healthy schools, we also need to be thinking thoughtfully about what constitutes an environment. More than just the school building, learning environments are shaped by the relationships and systems within it – which is why we love the Whole School Sustainability Framework’s inclusion of Education Programs and Organizational Culture. Without support from school administrators and students, healthy schools are not possible. Not only do we want to create healthier learning environments for all students – we also want to promote a culture of sustainability where schools play an active role in resource conservation and environmental stewardship!

Socioecological Model

The last theory we’ll share is the Socioecological Model – a hallmark of community-based public health practice! The Socioecological Model shows how health happens at all levels in which our society is organized – at the individual, intra-personal (relationships), community, and societal levels.

On the Rural Health Information Hub, they explain the levels of this model below:

- Intrapersonal/individual factors, which influence behavior such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and personality.

- Interpersonal factors, such as interactions with other people, which can provide social support or create barriers to interpersonal growth that promotes healthy behavior.

- Institutional and organizational factors, including the rules, regulations, policies, and informal structures that constrain or promote healthy behaviors.

- Community factors, such as formal or informal social norms that exist among individuals, groups, or organizations, can limit or enhance healthy behaviors.

- Public policy factors, including local, state, and federal policies and laws that regulate or support health actions and practices for disease prevention including early detection, control, and management.

We know that change does not happen in a vacuum. Change always happens in conversations within different systems in a school. The most effective public health programs work at all levels of the socioecological model. At Healthy Schools PA, we strive to cultivate individual relationships with school stakeholders, including parents, students, educators, and administrators. We train and educate community members on environmental health hazards, and we also advocate for societal or policy level solutions to protect children’s health!

Sources:

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm

https://centerforgreenschools.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/Whole-School_Sustainability_Framework.pdf

https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/2/theories-and-models/ecological

Celebrating Successes at the 4th Healthy Schools Summit!

Our 4th Annual Healthy Schools Summit was our biggest gathering yet! With over 60 educators, school administrators, parents, school board members, school facilities and custodial staff and community partners – we were so happy to host members representing each part of our growing network of healthy school advocates.

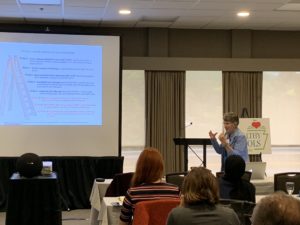

Erika Eitland, a PhD candidate and Program Manager of the Harvard University School of Public Health’s national laboratory for Schools for Health, was our keynote speaker. She shared the research linking the importance of healthy school buildings to student health, student cognition, and student academic performance. She also shared how making investments in school buildings can bring large, impactful returns on student wellness as a whole.

We also invited local leaders in school sustainability to join us for a Panel Discussion on what it takes to build healthy schools. Christine Schott, parent and Sustainability Coordinator for the Steel Valley School District shared her stories of success advocating for outdoor and garden education for all students in the district, as well some big wins for a district-wide recycling program! Jake Douglas, Food Services Director at Deer Lakes School District, discussed how the district makes it a priority to reduce waste in the lunchroom and support local farmers in their purchasing. Cassandra Brown, a school nurse at PPS Arsenal K-8 got a round of laughs and applause when she discussed her “Be a Thinker, Not a Stinker” program to improve personal hygiene education and access to a growing international student body population – bringing together innovative partnerships into the school to meet student needs in an empowering way. Vicki Ammar, a high school teacher at PPS Perry High School rounded out our panel, sharing an educator’s perspective for bringing partnerships and starting new initiatives within a school.

We had a networking and fun-filled working lunch, with Tracey Reed Armant, Program Officer at The Grable Foundation, presenting on “How to Write a Successful School Grant” from a Funder’s perspective.

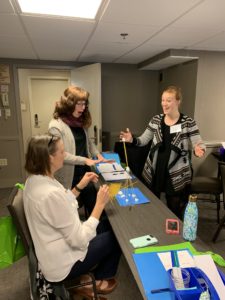

In the afternoon, we split into workshops to dive more in-depth. Katie Modic, of Communitopia, led our Educator Workshop, “Teaching Resiliency in the Classroom” which focused on hands-on climate education and bringing environmental justice into the classroom. Donnan Stoicovy, of State College Friends School, shared her school’s Zero-Waste journey and engaged participants in an interactive decision-making game for different school sustainability initiatives. LaKeisha Wolf, Director of Ujamaa/ Collective, and Monte Robinson, Community Schools Coordinator for the Pittsburgh Public Schools co-led our Parent and Partner Workshop on Engaging Parents and Partners for Healthy Schools. We all come to this work from different ways, and building on our shared goals has been central to pushing initiatives forward.

We left the Summit feeling excited for new connections, inspired by local rolemodels, and re-energized to continue the work towards building a healthy school for every child in our region!

To see presentations and workshop handouts from the Summit, please email Kara Rubio at Kara@WomenforaHealthyEnvironment.Org

Meet our KEYS Americorps Member, Evelyn!

My name is Evelyn, and I’m the newest addition to the Women for a Healthy Environment (WHE) team! I am serving with WHE as an AmeriCorps member until June 2020. AmeriCorps is a network of national service programs that take different approaches to improving lives and fostering civic engagement. My AmeriCorps program is called KEYS, which stands for Knowledge to Empower Youth to Success and is focused specifically on serving at-risk youth in Allegheny County through mentoring, tutoring, and community service in a variety of schools and community organizations. While KEYS members have been serving in Pittsburgh since 1995, I just moved here in August from Northern Virginia after obtaining my Bachelor’s degree in social work from James Madison University. I am incredibly excited to be serving here in such a diverse and lively city

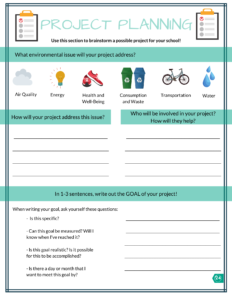

Through the KEYS program, my role with WHE is to facilitate Eco-Schools programming in Pittsburgh public schools. Eco-Schools is a program of the National Wildlife Federation that focuses on environment-based learning and hands-on experiences to empower students to make sustainable choices in their homes, schools, and communities. Students learn about air quality, water, energy, consumption, and other topic areas before brainstorming a school-wide project with the intent to improve their school’s environmental impact and become more sustainable.

Eco-Schools is the largest global sustainable schools program, reaching more than 50,000 schools worldwide! However, currently no Pittsburgh Public Schools are certified eco-schools. Our goal is to get a least one of these schools (if not more!) to become a certified eco-school before the 2019-2020 school year comes to an end. Through this program, schools have found creative and innovative ways to recycle, conserve, and reduce environmental impacts, which can have positive effects school-wide and ripple into the community as well!

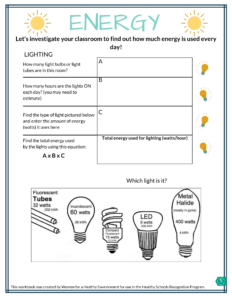

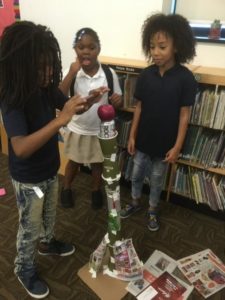

We have recently started our programming in Pittsburgh Faison K-5 in Homewood. We are enrichment partners with The Maker’s Clubhouse after-school program, and work with a group of 3rd-5th graders every Monday and Tuesday. Using STEAM and hands-on curriculum, these eco-students have explored the biodiversity on their school grounds, designed landfill liners, constructed towers out of recyclable items, conducted a school-wide energy audit, and learned about how our lungs work to defend our bodies against pollutants!

Next week, our students will learn about water quality and pollution, and will then attempt to construct their own water filters! Within a few weeks our students will be brainstorming project ideas for school sustainability. Whether our students choose to install rain barrels, create a pollinator garden, or start school-wide initiatives to conserve energy, our overall goal for this program is to teach our students that they can make positive changes in their schools and neighborhoods and empower them to continue to make sustainable choices to improve the overall well-being of their communities.

What is Integrated Pest Management?

Integrated Pest Management 101

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) revolves around six essential components: monitoring, recordkeeping, action levels, prevention, tactics criteria, and evaluation.

IPM is a program that reduces or eliminates the use of pesticides in order to minimize the toxicity of and exposure to harmful chemicals.

Over-reliance on pesticides exposes children and staff to dangerous chemicals. School IPM is a powerful tool for addressing these challenges. In fact, schools transitioning to IPM have reduced pest complaints and pesticide use by over 70%!

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends school IPM as a proven approach for creating healthy, safe spaces for students and staff.

Who regulates IPM programs in Pennsylvania? What are schools required to do?

School districts, intermediate units, area vocational-technical schools, and childcare centers are considered public places. As such, they are required by state law (Act 36 of 2002) to develop an IPM plan. The Pennsylvania IPM Program is administered by the Penn State Extension.

School IPM requirements are enforced by the Health and Safety program of the Department of Agriculture (PDA). This program manages the registration of pesticide products as well as the certification of pesticide applicators. There are regional PDA offices that manage pesticide applicator licenses – and only licensed applicators are allowed to spray pesticides on school grounds. In addition, schools are required to post clear signage on school grounds and communicate with the school community about the dates of pesticide application (at least 72 hours before application is scheduled to begin).

What does the research say about pesticides and children’s health?

Pesticides can cause short and long term health risks. Exposure can lead to pesticide poisoning, which is under-diagnosed in the U.S. According to the American Association of Poison Control Centers, about 10,000 children experience pesticide poisoning each year. Nationally, children between 6-11 years are found to have higher levels of pesticide residue in their bodies than any other group of people.

Of the 40 most commonly used pesticides in schools, 28 are known carcinogens, 14 are linked with

endocrine disruption, and 26 could lead to adverse reproductive effects. Recent research shows the use of RoundUp, a popular pesticide containing glyphosate, is becoming more and more common in schools. The World Health Organization declared in 2015 that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen.

What is the Hypersensitivity Registry and how do I sign myself/my child/my family members up?

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PDA) maintains a registry of individuals

hypersensitive to pesticides. It is a listing of locations for people who have been verified by a

physician to be excessively or abnormally sensitive to pesticides. These hypersensitive individuals

may request to have listings of their home, place of employment, school (if a student), and vacation

home placed in the Registry.

Once you are listed in the Registry, pesticide businesses are required to make notifications to you

12 to 72 hours in advance of any pesticide application to an attached structure or an outdoor above

ground application that they may make within 500 feet of any location that you have listed in the

Registry. The notification may be made by speaking to an adult through personal contact, by

telephone contact, leaving a message on your answering device, by certified mail, by posting a

notice on the front door at the listed location or speaking to an adult at the alternate phone number

you listed in the Registry.

The business must provide you their: business name, address, telephone number, the

pesticide brand name and common name (if available), EPA Registration number of the pesticide,

the location of the application and the proposed date and time of the application. The proposed

application time may not exceed a 24-hour period.

Obtain an application, which is available online, from your local

pesticide businesses, or by contacting any PDA Office (listed on the back). Make arrangements with

someone to be your alternate contact point. This person must be willing to receive calls when

applicators cannot contact you directly and forward the information on to you.

What else can I do as a concerned parent/teacher/student/school administrator/community member?

Meet with your school’s PTA and administrative office to ask about their IPM policies. PA state regulations require schools to implement IPM plans and alert parents and staff of chemical pesticide application prior to use. Request your school district to list the pest management company they use when pesticide application is required, and have them publicly share a list of pesticides to be used prior to application.

Work with your local Parent Teacher Association and school administration office to encourage your school to adopt a “no pesticides” policy for school grounds and help choose safer alternatives for pesticides when pesticides must be used.

Ensure that staff applying pesticides in your school are licensed by the state of PA. IPM plans often fail because school staff are not properly educated on the purpose and benefits of IPM strategies as opposed to pesticides.

Healthy Schools PA is proud to offer free technical assistance and training to school districts who want to create stronger IPM programs in their schools or child care centers. Contact us at info@healthyschoolspa.org if you are interested in learning more!

Good Up High but Bad Nearby: The Facts on Ground-level Ozone

You may have remembered learning about ozone in elementary school. Ozone is a odorless and clear gas made up of 3 oxygen atoms. Ozone gas makes up an entire layer in our atmosphere, where it protects our Earth from harmful UV rays. A few years ago, scientists and citizens grew concerned about an emerging hole in the ozone layer. Recent studies show that our ozone layer is repairable and that the hole in our ozone layer is closing year by year.

Ozone can also form closer to the ground. Ground-level ozone is created through a chemical reaction between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). NOx and VOCs are released by cars, power plants, refineries, and other industrial sources. When heated by sunlight, ground-level ozone is created. This is why ground-level ozone levels can get especially high during warm, sunny days.

What are the health effects of ozone?

Ozone is harmful to both humans and the environment. Exposure to ground-level ozone can create many respiratory problems in all individuals, including wheezing, cough, chest pain, throat and nose irritation, and inflammation. Long-term exposure to ozone can actually scar lung tissue and damage your lungs. Children are especially vulnerable to high ground-level ozone because they are lower to the ground, breathe more air per pound, and their lungs are still developing.

Ozone can also negatively affect the health of active adults, the elderly, and those with immune-compromised diseases and asthma.

Take action to protect your health on high ozone days.

There are several actions you can take to protect your and your loved one’s health during days where ground-level ozone is high.

- Staying indoors and avoiding high-exertion activities are recommended.

- Carpool with friends and family members if you are running errands or getting places.

- For children with asthma, make sure asthma controller medication is nearby or taken before going outside.

- Avoid burning wood fires or burning trash.

- Conserve electricity and avoid doing yard work with gasoline-fueled tools.

Sources:

https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/ground-level-ozone-basics#wwhhttps://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=resources.whatyoucando

Safer Sports Fields: A Win for Healthy Schools!

More and more recently, PA schools are opting to install artificial turf sports fields without considering the benefits of a natural grass field.

Often, the arguments against natural grass fields rely on the perceived costs and efforts of maintaining a natural grass field. But natural grass fields, when maintained with a specialized plan combining best practices of drainage, soil aeration, and grass selection, can sustain high usage while reducing hours of maintenance. Best of all, grass fields are often safer and healthier for student athletes to play on. We have come a long way in understanding the science behind maintaining a successful high-use grass sports field, including choosing grass that fits your school’s unique environment, and using innovative techniques so that groundskeepers and field managers work smarter, not harder.

You can watch our video with pediatrician and children’s environmental health expert Dr. Phil Landrigan discussing artificial turf in schools here.

Artificial turf fields can come with a host of unintended negative consequences. Depending on the in-fill material, artificial turf fields can release a long list of toxins when heated. Crumb rubber, made from recycled tires, and synthetic rubber, remain the most common in-fill materials for artificial turf fields. When heated, these rubber-based fillers can release 1,3-Butadiene, a major chemical component of tires – that burnt rubber tire smell – and a known carcinogen. Butadiene is not the only chemical released when rubber in-fill is heated; a meta-analysis by the Environment and Human Health Inc. found 92 chemicals of which 11 are known carcinogens.

Another health hazard that comes with artificial turf fields are the extreme temperatures that they can reach. On hot days, artificial turf fields absorb and hold heat, and can reach temperatures up to 190 degrees Fahrenheit really quickly. A turf field study by the University of Arkansas found that when the outdoor ambient temperature was 98 degrees Fahrenheit, an artificial turf field read at 199 degrees Fahrenheit – 100 degrees hotter! These sustained high temperatures have caused heat stroke and dehydration for student athletes, especially for younger school-aged children who are playing hard.

Lastly, artificial turf fields also need to be maintained. If in-fill isn’t continuously replaced, the risk for concussions can increase. The in-fill pieces are small and can be kicked up, cause scrapes and bruises. Turf fields also use a variety of chemicals to be maintained. Since most artificial grass and in-fill are made of flammable materials, harmful flame retardants are often added. Disinfectants are also sprayed on these fields as a recommended preventive maintenance activity.

Some communities are beginning to proactively ban crumb rubber artificial turf fields. If your school is looking for a new sports field to sustain high-use and longer play times, push your school board, athletic directors, and buildings and grounds directors to consider some alternatives. The Toxic Use Reduction Institute has an evidence-based booklet presenting the newest evidence and comparing different in-fill alternatives.

“A Healthy School for Every Child”: National Healthy Schools Day 2019

We are excited to join together with the Healthy Schools Network to celebrate National Healthy Schools Day this year! National Healthy Schools Day is a celebration of the progress we’ve made so far – but also a call to action to continue our work towards our shared goal of “a healthy school for every child”.

At Healthy Schools PA, we work collaboratively with parents, teachers, custodians, and school administrators every day as we strive towards this goal. Whether we’re teaching in classrooms, speaking at faculty and school board meetings, or providing technical support to school districts across Southwestern PA, we are constantly reminded of how special working in the school environment is. There are so many unique opportunities for folks to get engaged, get involved, and take action in their schools!

In September 2018, we released a first-of-its-kind report, “The State of Environmental Health in Southwestern PA Schools”, taking a deep look at how our schools were addressing environmental health concerns such as asthma, radon, lead, and air quality. This report highlighted the need for us to support our school districts at a federal, state, and regional level so that they have the resources and education necessary to make decisions about creating healthier school environments. We are tireless advocates for smart policy decisions that not only provide guidelines for schools to implement healthier practices, but that also provide appropriate resources for schools to enact real, long-lasting change.

Thanks to a generous grant from the Heinz Endowments, we have been able to impact change in schools across our region through our 1,000 Hours of Lead and Radon Free Schools and Childcares program. Working together with school districts, we have provided financial and technical support to schools and childcare centers to test and remediate the lead and radon hazards in their buildings. We have partnered with schools every step of the way, from scheduling testing and creating a drinking water or radon sampling plan, to interpreting test results, to providing different options for remediation according to the EPA’s federal guidelines. What we’ve learned from these projects and these processes is that it takes collaboration across departments to make sustainable change. Change comes when we empower school community members to ask questions, get educated on the issues, and make informed decisions together, in an open, transparent process.

Next May, we are celebrating the 4th year of our annual Healthy Schools Recognition Program – highlighting the efforts individual schools and districts are taking to ensure that children have a healthy place to learn, grow, and play. If you or your school are taking steps to be green or healthy, we’d love to hear and celebrate your story and help you along your journey!

Every child deserves a healthy school. Join us as we make this a reality for schools across PA and across our nation!

To read our State of the Schools Report, click here.

To learn more about our 1,000 Hours program, click here.

To participate in our Healthy Schools Recognition Program, click here.

Speak Out to Get the Lead Out!

Yesterday, our Executive Director, Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis delivered public comments at the Pittsburgh City Council’s meeting discussing lead in schools. Read them below:

“Good afternoon. I am Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis, executive director of Women for a Healthy Environment. Through education, technical assistance and advocacy our organization addresses environmental exposures that impact public health, including the neurotoxin lead.

Pittsburgh has a long tradition of focusing on lead exposure. One of the leading scientists and physicians in this area spent the majority of his career a few miles down the road in Oakland conducting research studies on the neurodevelopmental damage caused by lead poisoning. Dr. Herbert Needleman was credited with having played the key role in triggering environmental safety measures that have reduced average blood lead levels by an estimated 78 percent between 1976 and 1991.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization and many others, no amount of lead exposure is considered safe for children. We know that we need healthy spaces for children to be able to thrive, to excel in school.

1000 hours a year – that is the average amount of time students spend in school. And it is our job to make certain that during those hours, every occupant in the building, the student, the teacher (including pregnant women), the administrator, the staff member including school nurse, cafeteria worker and custodian are in the healthiest environment possible. Since the launch of 1000 Hours a Year in 2017, our Healthy Schools PA program has worked with twenty-one school districts, by assisting with the testing and remediation of lead in drinking water in schools. To those districts and others that have acted on this issue, and prioritized protecting the health of their school community, we commend you.

What we have learned through the 1000 Hours a Year initiative is that every single school that has been tested, showed the presence of lead – perhaps it was in the service line, the faucet, fixtures, the solder. But the good news is this is a completely preventable, solvable issue. We can fix this.

Our Healthy Schools PA, State of the Schools report released last fall told us that schools across southwestern PA are on average 66 years old. It’s time to stop the blame game or to be afraid to address this significant issue. Lead in schools is part of our aging infrastructure. We also found that some school districts were relying on their municipal water authority’s consumer confidence report to understand risk of lead exposure. We recommend schools do not rely on the water authority’s sampling data. The authority’s sampling data is based on a random sample of homes and is not reflective of potential lead-based water contamination risks in a school. Schools must address lead in drinking water, site specific.

So now is the time to call for action. It doesn’t cost an exorbitant amount of money to install filtered drinking water stations in every building, to turn off access to sinks in classrooms, and install filtering units on school cafeteria sinks. We need funding at the federal and state level to support schools so they can update and repair the aging infrastructure in these buildings. This is a community-wide problem, and we need to community-wide support to resolve it.

I would urge you to contact your school to ask about the status of testing and remediation. I would urge you to contact your elected officials to let them know this is an issue that demands attention and financial support. I would urge to join the Lead Safe Allegheny coalition that prioritizes primary prevention of lead and taking action at the local level. We can do better, we must do better for the sake of our children. Let’s honor the legacy of Dr. Needleman and commit to owning and addressing lead exposure and making a commitment to change. Thank you.”

To learn more about our 1,000 Hours a Year program, click here.

Lessons Learned from Seeds of Change Conference

Last week, I had the incredible opportunity to attend the 3rd Annual Seeds of Change: Igniting Student Action for Sustainable Communities conference at the beautiful Eden Hall Campus of Chatham University.

The Seeds of Change conference brings together students from schools across the region to share, collaborate, and reimagine a more sustainable world. Class projects organized around the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals showcase students’ skills in bridging interdisciplinary knowledge. A keynote lecture by Ariam Ford, a city planner consultant, set the tone for the uplifting and inspiring conversations that were to come.

From the group of students I was invited to learn from, I heard about:

- how a school building can be used as a tool for learning and practicing sustainability (Eden Hall Upper Elementary School – Pine Richland School District),

- how a workforce development program through Operation Better Block helps provide high schoolers with skill-building and community engagement (Homewood and Braddock communities),

- how community art initiatives can bring people together to help reimagine what development in their neighborhood could look like (Nazareth Prep),

- how 5th and 4th graders can bridge their disagreements and work together to make their very own pallet garden (Manchester Academic Charter School), and

- how high schoolers at City Charter school are envisioning a way to make home and community gardening more accessible to folks in their communities.

And these were only 5 of the 18 excellent presentations given that day, to adults working in industries as varied as public transportation, community art, facilities management, higher education, and local government.

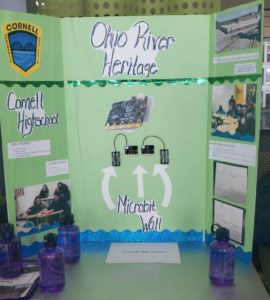

Pictured above: Two poster boards on the Ohio River Watershed and Wildfire Prevention.

We ended the day with a listening session, where students explained to the adults in the room what their vision was for a sustainable Pittsburgh, and a sustainable world. Every day, these students are learning how to think through impossible problems, and break them down into ways they can act locally. They are problem solvers. They are goal-setters. Most importantly, they are committed to leaving this planet better than how they found it – and we adults have a lot to learn from their example.

In our day to day work, it can often feel like holistic, equitable, and impactful sustainability is just beyond our reach. Fighting for change can be a real uphill battle. But these students remind me that we have a responsibility to act. We have the power lift each other up. We have the ability to work together, racing towards our shared vision of just, green, and equitable world. These lessons move beyond the classroom and have the power to change our relationships with one another, and with our planet.

I want to thank Chatham University, Eden Hall Campus for the opportunity to be able to attend and moderate a session of the Seeds of Change conference. To learn more about Chatham University’s K-12 Educational Programs, click here.